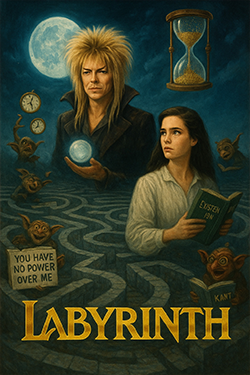

Labyrinth: Kierkegaard with Puppets, Bowie with Glitter

In Labyrinth (1986), Jim Henson presents us with a riddle disguised as a movie, a glitter-soaked allegory for the eternal tension between adolescent angst and metaphysical responsibility. Sarah, our moody heroine, essentially reenacts Sartre’s No Exit, only instead of three people in a room, it’s one teenager wandering through a Muppet-sponsored fever dream. The labyrinth itself is less a maze than a practical demonstration of Zeno’s paradox, where each step towards adulthood is halved by David Bowie’s hairline.

Speaking of Bowie, his Goblin King is philosophy’s greatest gift: a Dionysian figure who dances in tights and reminds us that power, like eyeliner, is all about application. He tempts Sarah with glittery dominion, proving Nietzsche’s theory that the will to power occasionally comes accessorized with a riding crop. Yet Sarah resists, clinging instead to the Kantian categorical imperative, apparently, you shouldn’t abdicate babysitting duties, even if the alternative involves an eternal masquerade ball with the Thin White Duke.

The film’s conclusion, in which Sarah declares, “You have no power over me,” is a proto-existential mic drop. Here she rejects both authority and glam rock seduction, choosing instead to embrace personal responsibility, though notably she does so only after being serenaded by a chorus of goblins. Henson’s lesson is clear: maturity means accepting the absurdity of life, while still partying with puppets when the moment calls for it.

Thus, Labyrinth is less a children’s fantasy and more a philosophy textbook wrapped in leg warmers: Kierkegaard with muppets, Nietzsche with mascara, Plato with puppets.