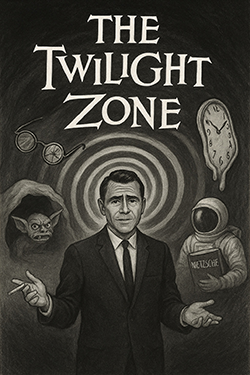

The Twilight Zone: Kant Walk Into the Twilight Zone Without Tripping Over Irony

To speak of The Twilight Zone is to stumble into a Kantian funhouse where moral imperatives are tested by gremlins on airplane wings. Rod Serling, the chain-smoking oracle, opens each episode not merely as a host but as a low-rent Plato, ushering viewers into a cave where the shadows wear fedoras and sell you insurance policies with ironic consequences.

The genius of the show is its consistent philosophical bait-and-switch. You begin thinking you’re watching a melodrama about suburban ennui, but five minutes later, you discover you’ve actually been enrolled in a crash course on existential dread. Sartre may have claimed “hell is other people,” but The Twilight Zone insists hell is actually yourself, realizing too late that you wished on the wrong cursed trinket at the antique store.

Each twist ending functions like a Socratic dialogue cut short by an unexpected punchline. The criminal who believes he’s escaped justice? Surprise: he’s been sentenced to spend eternity with his own smug self. The lonely bookworm who craves infinite reading time? Dialectical justice breaks his glasses. The astronaut longing for freedom? He’s already trapped in a cosmic DMV.

What Serling ultimately proposed was a TV universe governed not by Aristotelian logic, but by cosmic irony, where every desire is punished with the fervor of a moral fable written by Nietzsche on Ambien.

In short, The Twilight Zone is less a show and more a weekly reminder that existence itself is a joke, just one delivered in 25 minutes, with eerie theremin music.